Surface charging of Jupiter’s moon europa

Reddy, Nordheim, and Harris (2024)

1. Introduction & Motivation: Europa in Jupiter’s plasma

What are the electric potentials that develop on Europa’s surface?

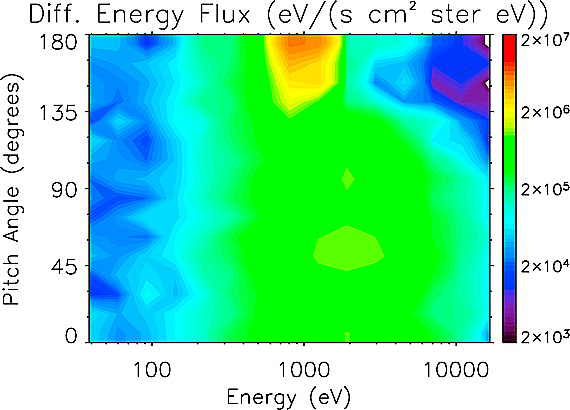

Why Europa is special? Europa sees two plasma populations at once:

- Not shielded by a thick atmosphere => bombardment from the comparatively hot and tenuous Jupiter’s magnetospheric plasma

- Ionosphere extends to the surface => exposed to both dense and cold ionospheric plasma

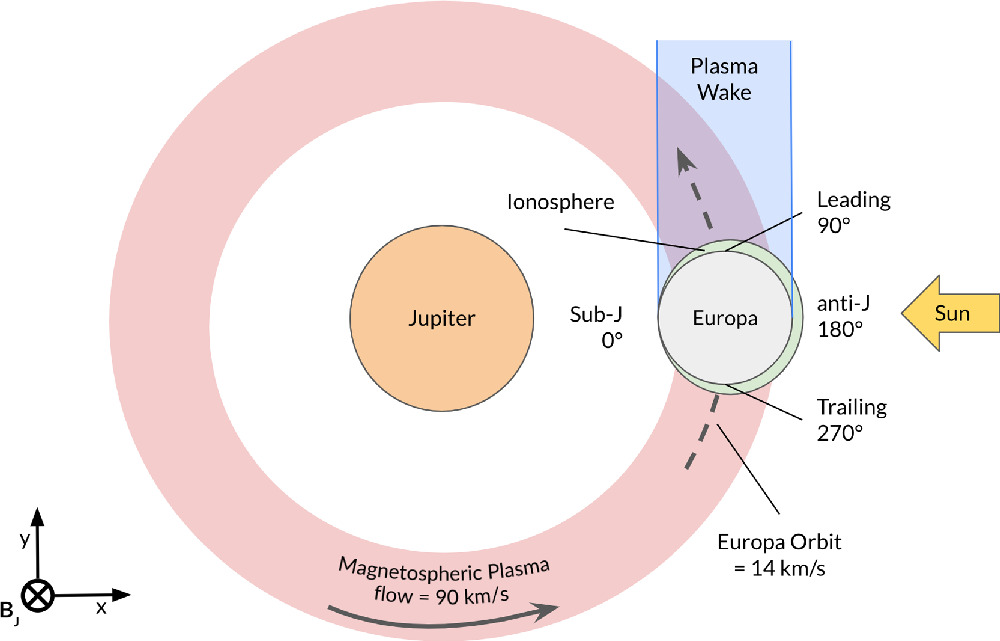

Also, Jupiter’s plasma flows past Europa at 90 km/s (Europa orbits Jupiter at 14 km s⁻¹), so different hemispheres see very different bombardment.

The physics model

Europa’s surface charges until all currents balance:

\[ I_e(\phi)-I_i(\phi)-I_s(\phi)-I_{ph}(\phi)=0 \]

where

- \(I_e\): Plasma electrons hitting surface

- \(I_i\): Plasma ions hitting surface

- \(I_s\): Secondary electrons emitted from ice

- \(I_{ph}\): Photoelectrons from sunlight

- \(\phi\): Surface electric potential

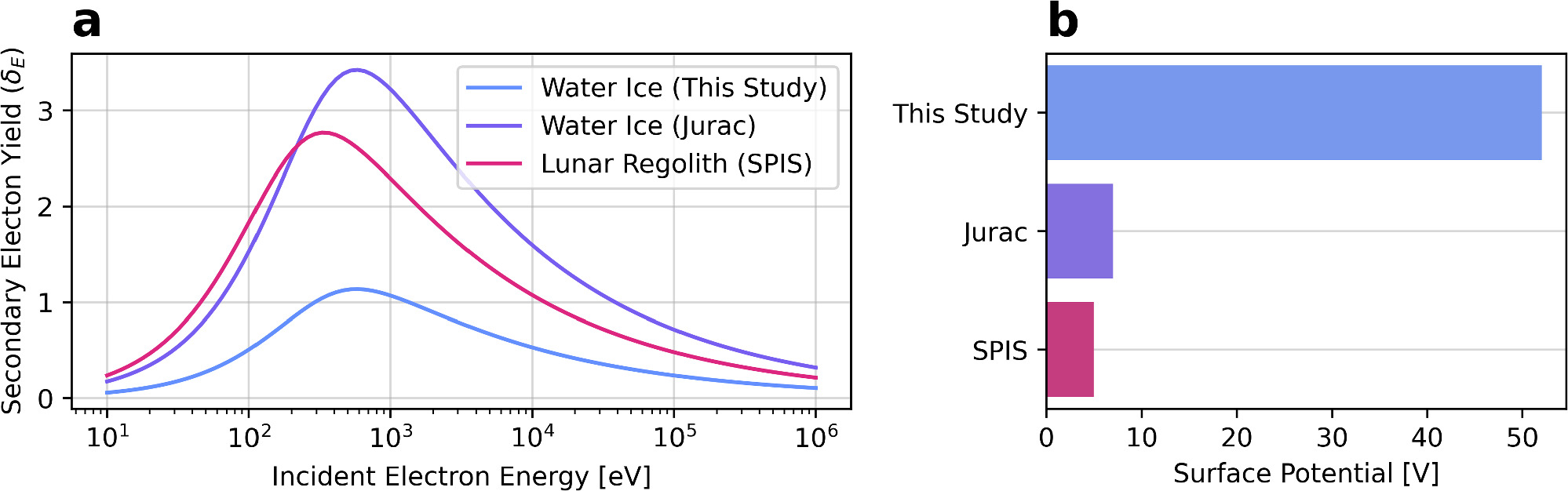

2. The physics model: material parameters and secondary electron emission

Ice emits electrons when hit by energetic electrons.

\[ \delta(E) \equiv \frac{\text{number of electrons emitted from the surface}}{\text{number of electrons that hit it}}. \]

They use the Katz formula (1977):

Nearly all of the energy lost by an incident electron goes into electronic excitations, and we assume the probability of an electronic excitation resulting in an escaped secondary varies exponentially with depth.

\[ \begin{aligned} \delta(E, \theta) & = c_1 \int_0^{E d R / d E}\left(\frac{d R}{d E}\right)^{-1} e^{-c_2 x \cos \theta} d x \\ & =\frac{c_1\left[1-\exp \left(-c_2 \cos \theta E d R / d E\right)\right]}{c_2 \cos \theta d R / d E} \end{aligned} \]

The angle averaged yield then becomes \(\bar{\delta}(E)=2 c_1 E(Q-1+\exp (-Q)) / Q^2\)

\[ \delta(E)=5.08,\delta_{\max}\frac{E}{E_{\max}}\frac{Q-1+e^{-Q}}{Q^2}, \quad Q=2.28\left(\frac{E}{E_{\max}}\right)^{1.35} \]

They adopt:

- the peak value of the yield: \(\delta_{\max}=0.78\) (reduced from lab ice due to roughness)

- the energy at which emission peaks: \(E_{\max}=340\) eV

- a nonlinear measure of how deeply electrons penetrate into the surface: \(Q=2.28\left(\frac{E}{E_{\max}}\right)^{1.35}\)

The secondary electron current (I_s) is controlled by ((E)). If energetic electrons hit Europa and knock out many secondaries, Europa loses negative charge and becomes more positive. Thus ((E)) is one of the most important material parameters.

- Very low-energy electrons: little emission

- Intermediate energy: yield rises

- High energy: electrons penetrate too deeply → most secondaries are reabsorbed → yield falls

The factor \(\frac{Q - 1 + e^{-Q}}{Q^2}\) comes from transport theory: it models how secondaries created at depth escape the material.

It behaves like this:

- Low energy (small (Q)): \(e^{-Q} \approx 1 - Q \quad\Rightarrow \quad Q - 1 + e^{-Q} \approx \tfrac{1}{2}Q^2\)

So (E): yield rises linearly with energy.

- High energy (large (Q)): \(e^{-Q} \to 0 \quad\Rightarrow\quad \frac{Q-1}{Q^2} \sim \frac{1}{Q}\)

3. Simulation approach

They use SPIS, a 3-D Particle-in-Cell plasma charging code .

Europa’s surface is represented as a 1 m × 3 m cylinder embedded in plasma with:

- realistic electron & ion distributions

- magnetic field

- secondary electron emission

- photoemission

Four hemispheres are simulated:

- Sub-Jovian (0°)

- Leading (90°W)

- Anti-Jovian (180°)

- Trailing (270°W)

plus sunlit vs eclipse.

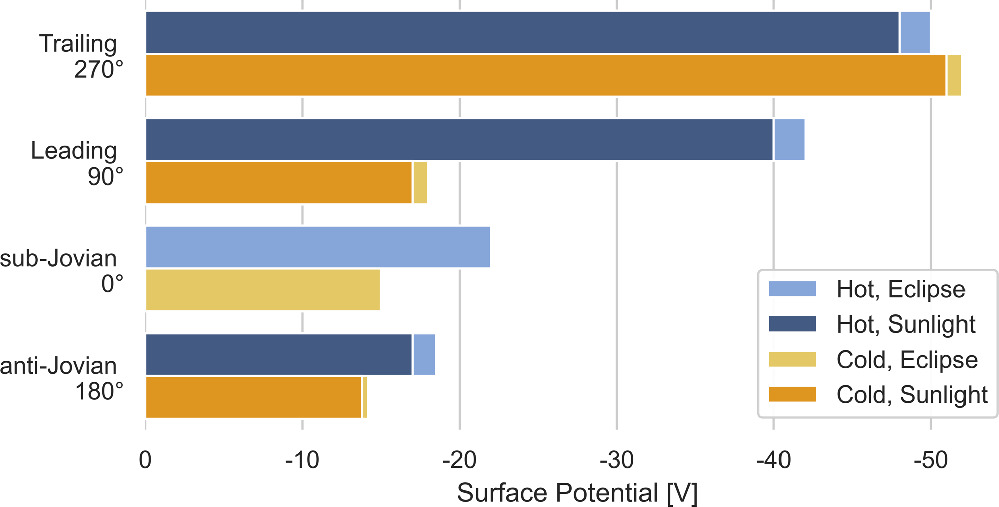

4. Main result: Europa is always negative

Predicted surface potentials:

\[ -14 \text{V} \to -52 \text{V} \]

depending on hemisphere, sunlight, and plasma environment.

| Location | Why |

|---|---|

| Trailing hemisphere | Faces plasma flow → strongest charging |

| Leading hemisphere | In plasma wake → fewer ions, more electrons |

- a hotter population results in a greater negative potential

- photoemission reduces the surface potential by up to 2 V (relatively small)

The sub-Jovian hemisphere is slightly more negative than the anti-Jovian side and this is due to the 14% decrease in the ionospheric density

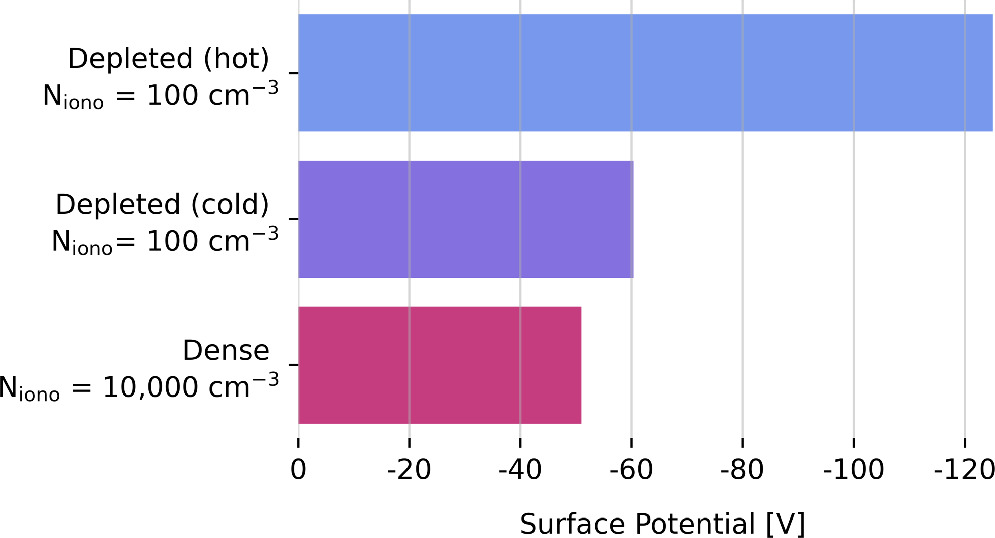

5. The ionosphere “dampens” charging

If Europa had less dense ionosphere, potentials would be much larger.

They reduce ionospheric density from 10,000 cm⁻³ to 100 cm⁻³ and find:

\[ -51 \text{V} \to -125 \text{V} \]

for hot plasma.

reduced ionosphere leads to a greater surface potential and this is especially the case with the hot parameters. This “ionospheric dampening” effect also acts to suppress surface potentials at the other hemispheres by a similar magnitude

6. Secondary emission dominates uncertainty

Changing the assumed surface material gives:

\[ -52 \text{V} \to -5 \text{V} \]

for the same plasma conditions.

So Europa’s chemistry (water ice vs salts, sulfuric acid, etc.) directly affects its electric environment.

7. Observational consequences and Why this matters?

Negative surfaces accelerate secondary electrons upward along magnetic field lines. These form electron beams detectable by spacecraft (representative of the electrostatic potential difference between the spacecraft and the surface). This was used at Earth’s Moon and Saturn’s moon Hyperion.

Same method could be used by Europa Clipper and JUICE to remotely probe surface composition using plasma instruments.

This makes surface charging a new diagnostic tool for Europa’s geology and chemistry.