Radio signatures of star–planet interactions, exoplanets and space weather

1. Introduction & Motivation

The Problem: Understanding the space environment around exoplanets is crucial for characterizing their potential habitability. This requires measuring stellar magnetic activity and space weather events (like CMEs).

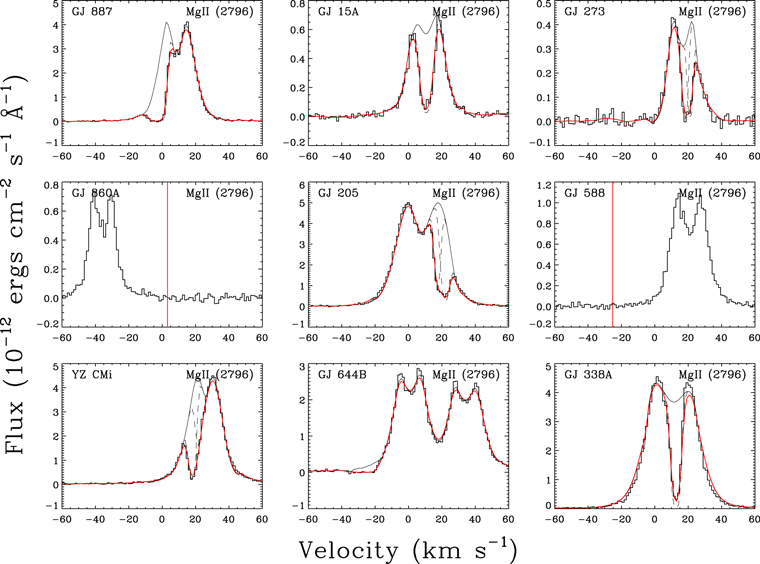

The Limitation of Other Wavelengths: X-ray and UV observations tell us about the star’s atmosphere, but radio detections offer a unique, sensitive window onto the star’s magnetosphere and the exoplanet’s own magnetic field and its interaction with the star.

The Paper’s Role: This paper is a primer designed to guide new researchers, detailing the physical mechanisms and recent observational advances in the field.

-

- radio free–free emission from the ionized coronal winds

- X-ray emission generated by charge exchange between the ionized wind and interstellar neutrals

- astrospheric Lyα absorption and absorption from the hydrogen wall

- bursty, low-frequency radio accompanying the CME

-

- auroral (radio) emission

Key Questions

- How can radio bursts (like those from the Sun) characterize stellar space weather and detect stellar CMEs?

- What is the role of magnetic Star-Planet Interaction (SPI) in producing observable radio signals?

- Can we directly detect the radio emission from an exoplanetary magnetosphere (like Jupiter’s aurora) and use it to measure the planet’s magnetic field?

2. Key Concepts & Mechanisms (The “How?”)

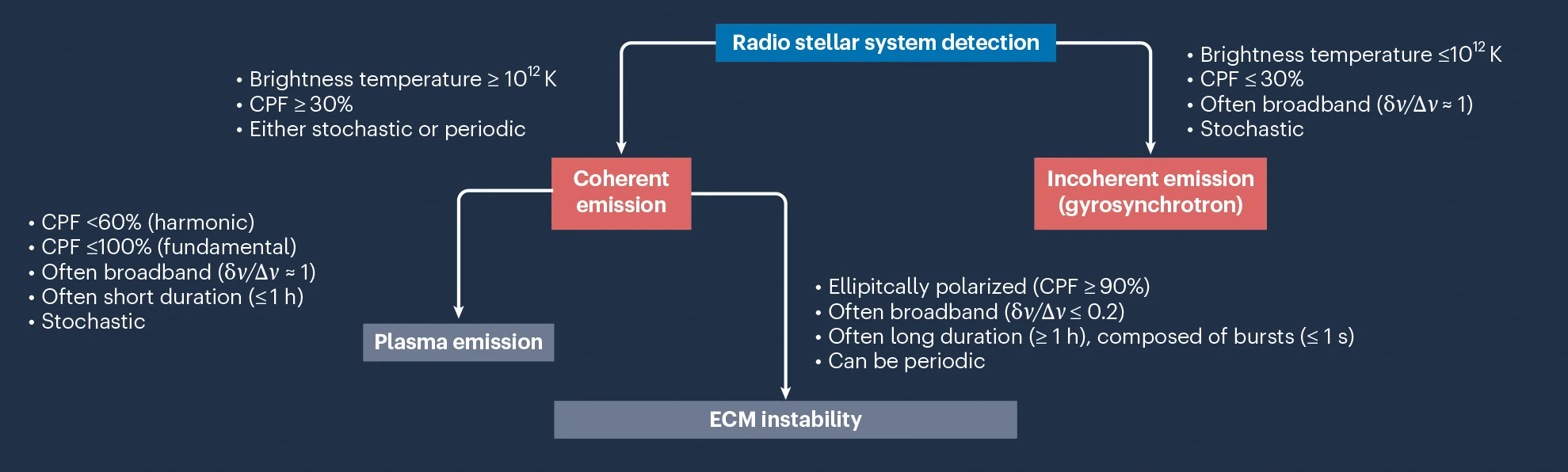

A. Radio Emission Mechanisms

Two main types of radio emission in stellar systems:

| Type | Mechanism | Physics | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incoherent | Gyrosynchrotron Emission | Generated by mildly-relativistic electrons spiraling in a magnetic field. | Associated with flares and active regions on the star. |

| Coherent | Electron Cyclotron Maser Instability (ECMI) | Generated by energetic electrons trapped in a magnetic field. All electrons emit in phase, resulting in extremely bright radiation. | This is the mechanism for stellar auroral emission, planetary auroral emission, and Star-Planet Interaction signatures. |

B. Solar System Analogues

The paper emphasizes using the Sun and Jupiter as templates:

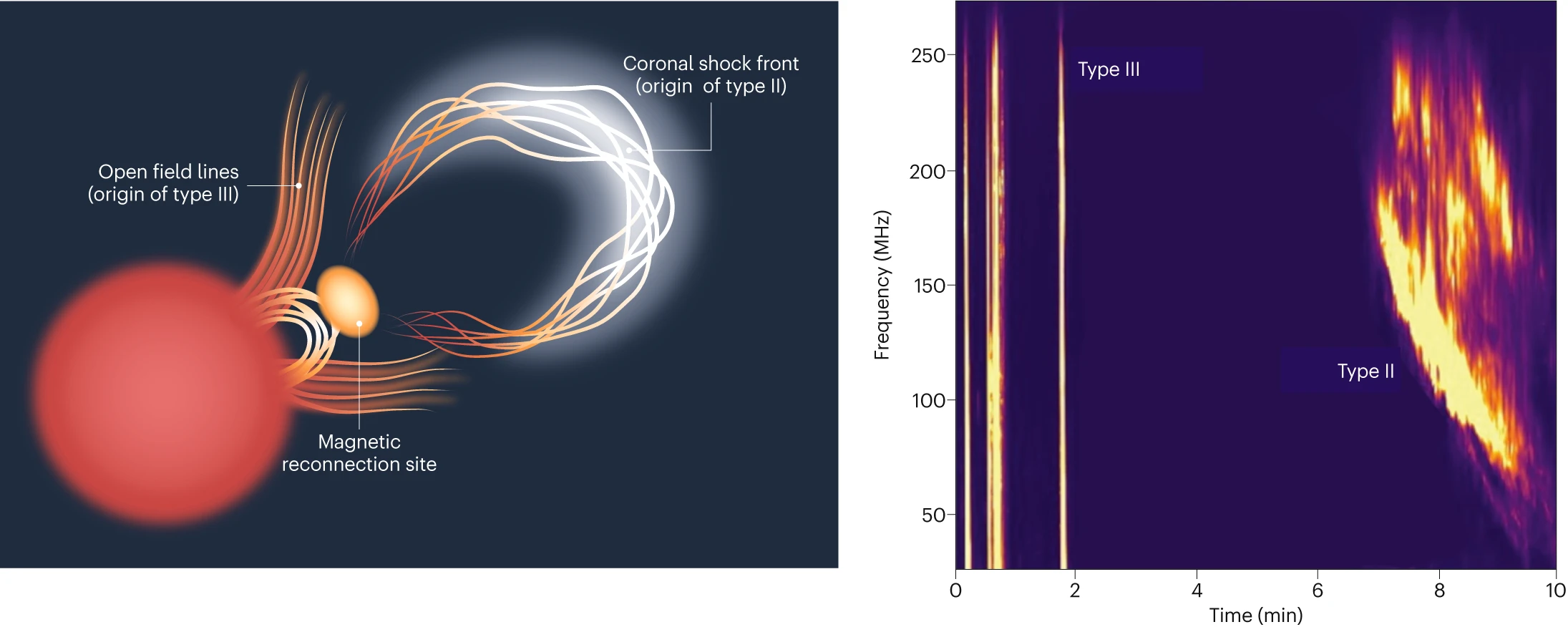

- Solar Bursts:

- Type II Bursts (minutes to hours) are associated with electrons accelerated by CME shocks. Detecting these in exoplanetary systems is the best way to characterize CMEs.

- Type III Bursts (short, seconds) are associated with electron beams from magnetic reconnection events.

- Jupiter’s Aurorae: The powerful, highly directional radio emission from Jupiter’s magnetic poles is the direct analogue for potential exoplanet auroral radio emission.

3. Observational Advances & Key Results (The “What?”)

A. Star-Planet Interactions (SPI)

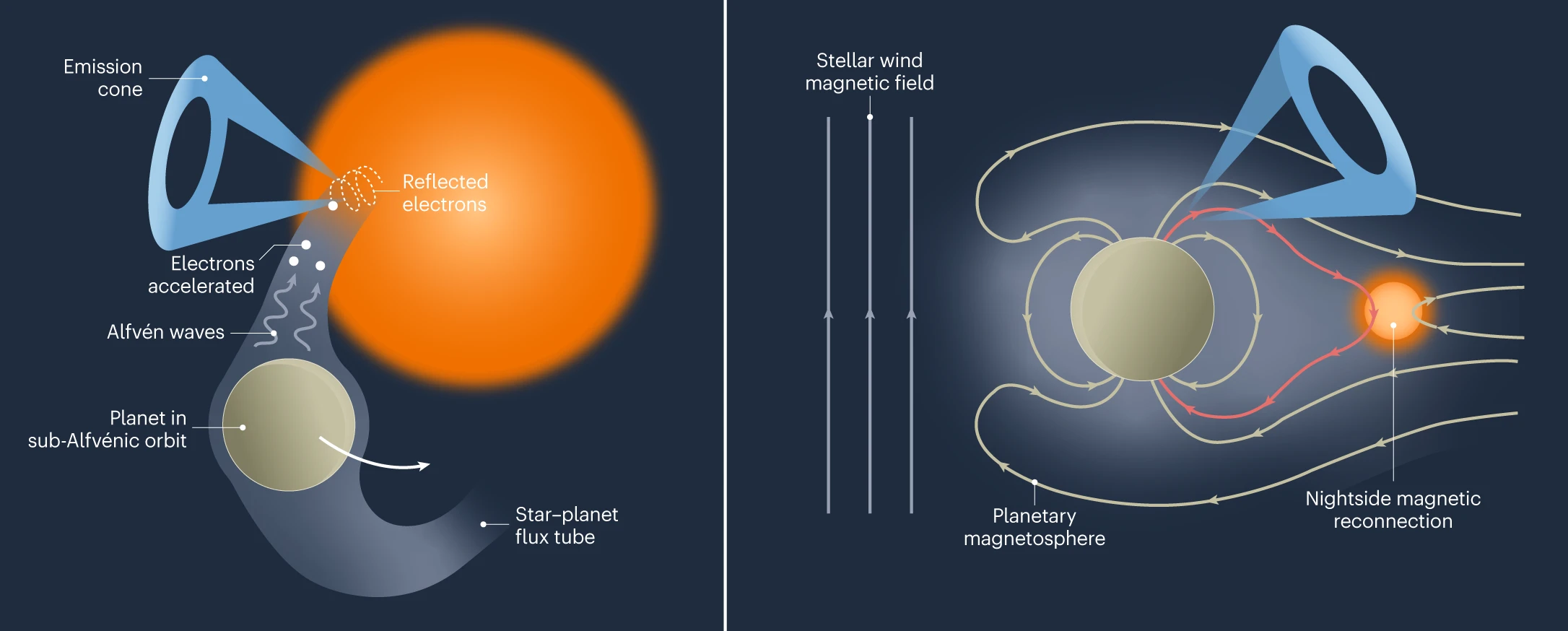

- Concept: When a close-in planet orbits within the star’s magnetosphere, the planetary and stellar magnetic fields can connect and accelerate electrons toward the stellar/planetary poles.

- Signature: This magnetic connection is predicted to generate bright, coherent radio bursts that are modulated (or synchronized) with the planet’s orbital period.

- Status: The paper reviews recent provisional detections of these SPI-induced radio bursts, highlighting their potential for characterizing exoplanet systems and their magnetic fields.

B. Direct Exoplanet Magnetosphere Detection

- Goal: To detect the radio aurorae generated by the exoplanet itself (ECMI emission).

- Significance: Detecting a planet’s magnetic field is crucial for determining its ability to shield its atmosphere from harsh stellar wind—a key factor for long-term habitability.

- Status: There are early tentative results hinting at the direct detection of exoplanetary magnetospheres.

C. Low-Mass Stars and Brown Dwarfs, Ultracool dwarfs (UCDs)

Since UCDs and giant exoplanets share a similar mass, radius, and dynamo mechanism (fully convective), the radio emission from the most massive exoplanets is expected to be governed by the same physics seen in UCDs.

- Low-Mass Stars: Advances have been driven by low-frequency radio instruments observing auroral emissions from radio-bright low-mass stars.

- Brown Dwarfs: These objects often possess very strong magnetospheres and are naturally radio-bright, making them easier targets for detailed study using current instruments, which helps validate the physical models used for exoplanets.

4. Discussion & Future Outlook

A. Implications and Unanswered Questions

- Space Weather: Time-resolved radio dynamic spectra offer the best way to detect and characterize CMEs from stars other than the Sun, which directly impacts exoplanet atmospheric escape.

- Exoplanet Characterization: Radio detections of SPI and planetary aurorae offer the potential to measure the magnetic field strength of exoplanets, a parameter inaccessible by other current methods.

- Theory Gaps: There are still outstanding questions in the theory of stellar, SPI, and exoplanet radio emission that require consolidation.

The naturation of new low-frequency radio instruments and wide-field surveys and future radio facilities (e.g., SKA, LOFAR upgrades) will be essential for moving beyond tentative results to definitive characterization of exoplanet magnetic fields and the surrounding space environment.

- Tentative vs. Confirmed: The paper relies heavily on “provisional” and “tentative” detections (especially for direct exoplanet emission and CMEs). Does the community need to agree on a stricter detection criterion?

- Model Dependency: How robust are the planetary magnetic field estimates derived from the radio observations, given they rely on models and analogies with Jupiter?

- Observational Bias: Is the field currently biased toward highly magnetic, active stars and close-in (Hot Jupiter) systems? How can we expand the target list?