Exploring solar wind discontinuity properties in the inner and outer heliosphere

PhD Candidate: Zijin Zhang

Abstract

Solar wind discontinuities, characterized by abrupt changes in the magnetic field, play a crucial role in heliospheric dynamics. This includes solar wind turbulence, particle heating, and acceleration. Understanding these discontinuities is essential for elucidating the fundamental processes that govern the solar wind’s evolution and its interaction with planetary environments. This proposal aims to conduct a detailed study of these discontinuities, leveraging data from contemporary space missions like Parker Solar Probe (PSP) and Juno to examine their characteristics (occurrence rates, thickness, current density, and Alfvénicity, etc.) from the Sun to beyond 1 AU. By analyzing the evolution of these features, this study seeks to answer questions about how the discontinuities change with radial distance from the Sun and the physical mechanisms behind their formation and evolution. Detailed observational information about their configuration and evolution will provide a solid foundation for investigations of the role of discontinuities in solar wind heating, energetic particle acceleration, and propagation.

Introduction and Background

Solar wind magnetic discontinuities, characterized by rapid variations in interplanetary magnetic fields, are pivotal in understanding key phenomena in heliophysics. These discontinuities, manifesting as localized transient rotations or jumps in the magnetic field, are among the first discoveries in solar wind investigations (Colburn and Sonett 1966). Theoretical models suggest that the formation and destruction of discontinuities are closely related to the nonlinear dynamics of Alfvén waves. These nonlinear processes can create significant isolated disturbances to the otherwise adiabatic evolution of the solar wind flow.

These discontinuities change the local direction of the interplanetary magnetic field (deviating from the average Parker spiral) and contribute significantly to the magnetic fluctuation spectrum (Borovsky 2010). They harbor kinetic-scale structures with intense currents, which act as a source of free energy for plasma waves and instabilities, leading to energy dissipation(Dmitruk, Matthaeus, and Seenu 2004; macbrideTurbulentCascade12008?; Osman et al. 2012; Tessein et al. 2013). Their formation, evolution, and destruction are believed to be closely related to solar wind heating and acceleration via magnetic reconnection (Dmitruk, Matthaeus, and Seenu 2004) or nonlinear wave-wave and wave-particle interaction (Medvedev et al. 1997). Moreover, discontinuities are coherent structures in turbulent solar wind and have a nontrivial influence (distinct from random fluctuations) on energetic particles whose gyroradius is comparable to the thickness of the discontinuity (Malara, Perri, and Zimbardo 2021). Recent investigation of the nonfluid (kinetic) properties of solar wind discontinuities (Artemyev et al. 2019) reveals that electron density and temperature vary significantly across these discontinuities, underlining the importance of kinetic effects in discontinuity structure.

Understanding the dynamics of solar wind discontinuities is essential for elucidating the fundamental processes that govern the solar wind’s evolution as it travels through the heliosphere. As such, this study aims to address the key question:

“How do discontinuities evolve over radial distances from the Sun and what are the physical mechanisms behind their formation and evolution?”

By leveraging data from missions such as PSP and Juno, this research will generate a comprehensive data set of discontinuity configurations and investigate their spatial and temporal evolution. These statistics will aid in modeling processes like ion scattering by coherent structures and elucidate their roles in solar wind heating and particle acceleration.

Previous Studies and Context

Spacecraft investigations of the space plasma environment have revealed that the solar wind magnetic field follows the Parker model of the heliospheric current sheet only on average. Localized transient currents, which can be significantly more intense than the model currents, are carried by various discontinuities observed as strong variations in magnetic field components (Colburn and Sonett 1966; Burlaga 1968; Turner and Siscoe 1971). Most often, such variations are manifested as magnetic field rotations within the plane of two most fluctuating components.

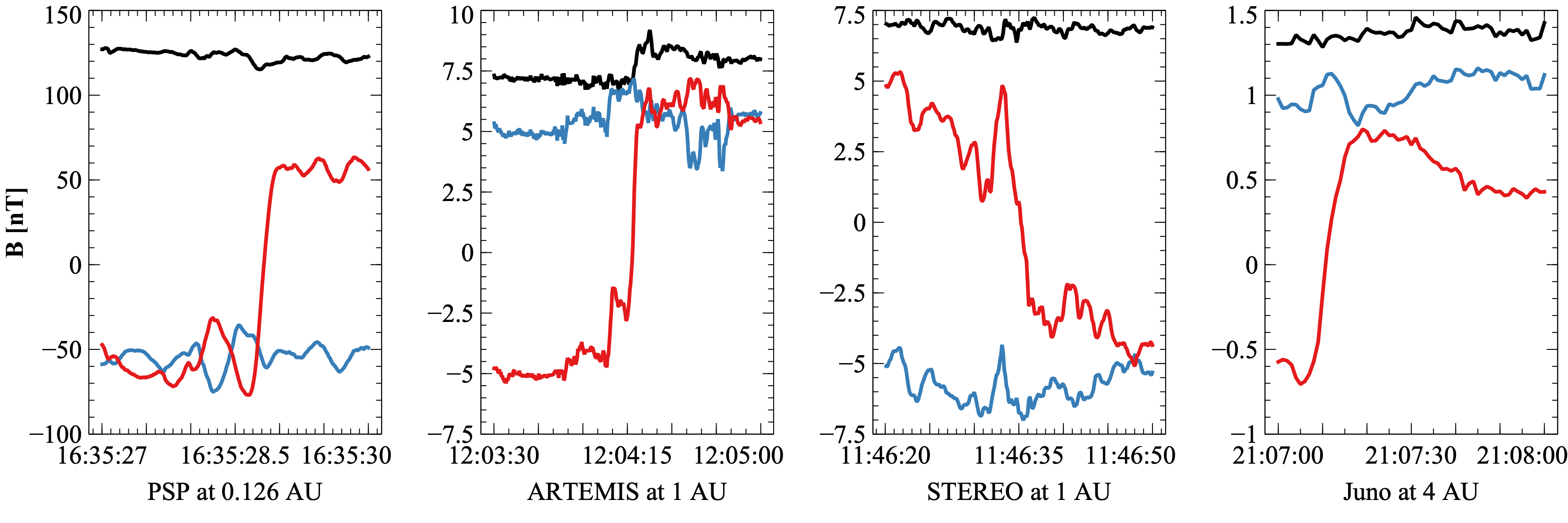

Further advancements were made with data from the Helios-1, Helios-2, Ulysses, and Voyager missions, which explored discontinuities in three-dimensional space, revealing their prevalence and importance throughout the heliosphere (Mariani, Bavassano, and Villante 1983; Tsurutani et al. 1997). As illustrated in Figure 1, these discontinuities are observed at a multitude of radial distances from the Sun. These findings underscored the need to understand the origin of discontinuities, which are thought to arise from dynamic processes on the Sun, including solar flares and coronal mass ejections, as well as through in-situ processes like local magnetic turbulence, magnetic reconnection, and nonlinear wave interactions within the solar wind.

The Role of Alfven wave and kinetic effects in the discontinuities

Ulysses measurements of the high-latitude solar wind at \(1-5\) AU showed that the majority of discontinuities resided within the stream-stream interaction regions and/or within Alfvén wave trains (Tsurutani et al. 1995; Tsurutani and Ho 1999). The nonlinear evolution of Alfvén waves (wave steepening) can be the main cause of such discontinuities. The background plasma/magnetic field inhomogeneities and various dissipative processes are key to Alfvén wave nonlinear evolution . In hybrid simulations and analytical models , this steepening was shown to cause formation of discontinuities in configurations resembling the near-Earth observations. There are models predicting discontinuity formation and destruction due to dissipative processes (e.g., Alfvén wave steepening, magnetic reconnection) in the solar wind. However, the efficiency of these processes in realistic expanding solar wind was not yet tested against observations.

More recently, utilizing high-resolution plasma measurements from ARTEMIS and MMS missions, Artemyev et al. (2019) showed that discontinuities have kinetic characteristics for both tangential and rotational discontinuities: fluxes of electrons of different energies vary differently across these discontinuities. These discoveries revealed the importance of ion and electron kinetics to discontinuity structure.

Current Gaps in Understanding

Previous observations of solar wind discontinuities in the outer heliosphere were rarely in conjunction with measurements closer to the Sun. Thus it is presently unclear whether the observed changes in their frequency and properties are due to variations in the solar plasma state resulting from solar variability, such as the solar magnetic activity cycle, or whether these changes are a natural outcome of the discontinuities’ propagation and interaction with the ambient solar wind.

Regular and long-lasting Juno (2011-2016) and PSP (2019-now) observations, together with almost permanent near-Earth solar wind monitoring, provide a unique opportunity to examine the discontinuity characteristics at two radial distances simultaneously in the context of both the inner and the outer heliosphere over a large radial distance range (\(\sim 0.1\) AU - \(\sim 5\) AU). We will determine the discontinuity occurrence rates and properties for various radial distances and compare these results with the prediction of the adiabatic expansion model to understand if discontinuity formation or destruction dominates the statistics of discontinuities far away from the solar wind acceleration region.

This research seeks to address these gaps by leveraging recent advancements in observational capabilities and numerical modeling to provide a comprehensive examination of solar wind discontinuities.

Methodology

Data Collection and Model:

Parker Solar Probe and Juno provide high-resolution magnetic field and plasma data from the inner heliosphere to beyond 1 AU. The PSP’s close passes to the Sun offer unique insights into the nascent solar wind, while Juno’s trajectory up to Jupiter allows for studying the evolution of solar wind structures as they propagate outward.

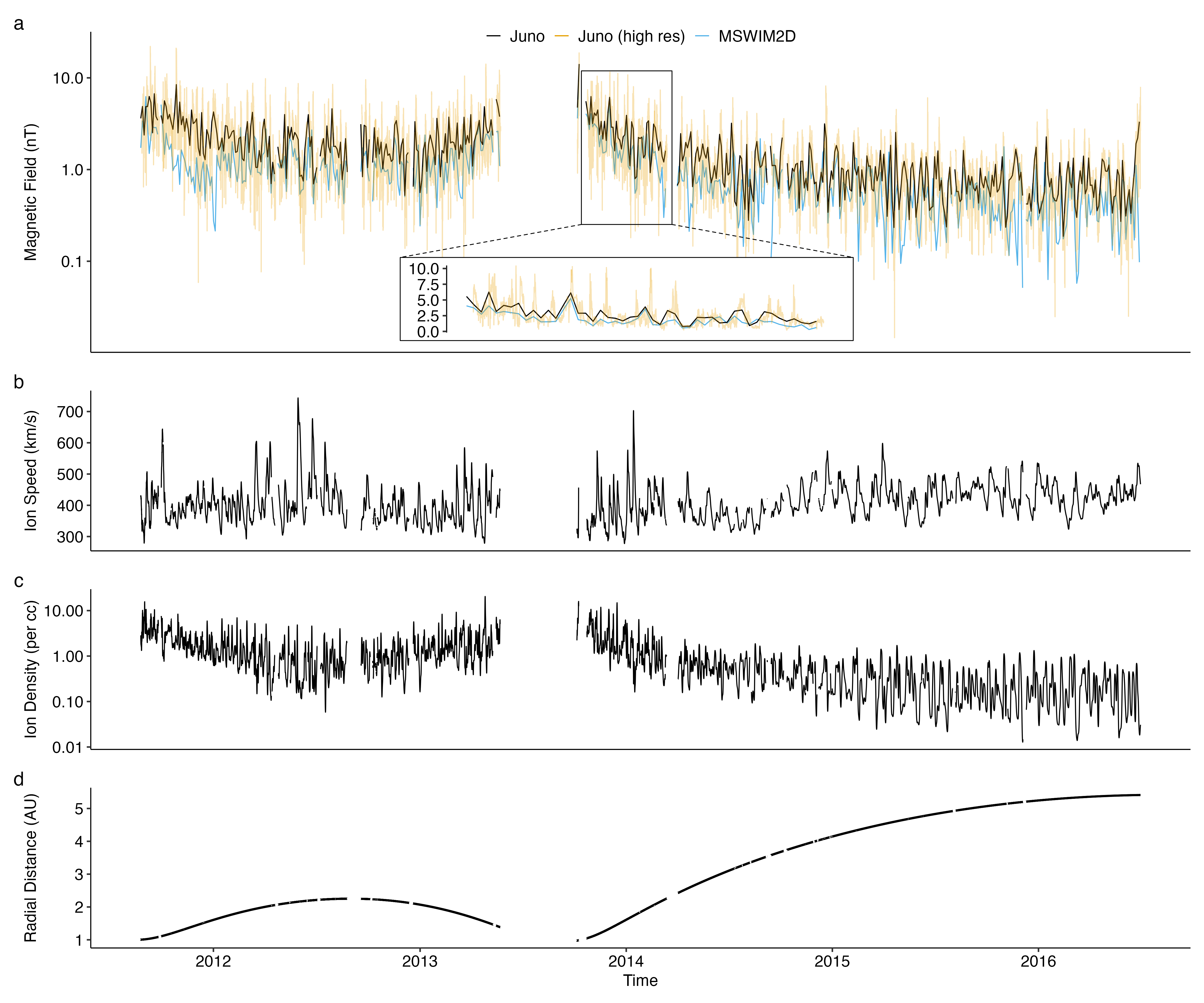

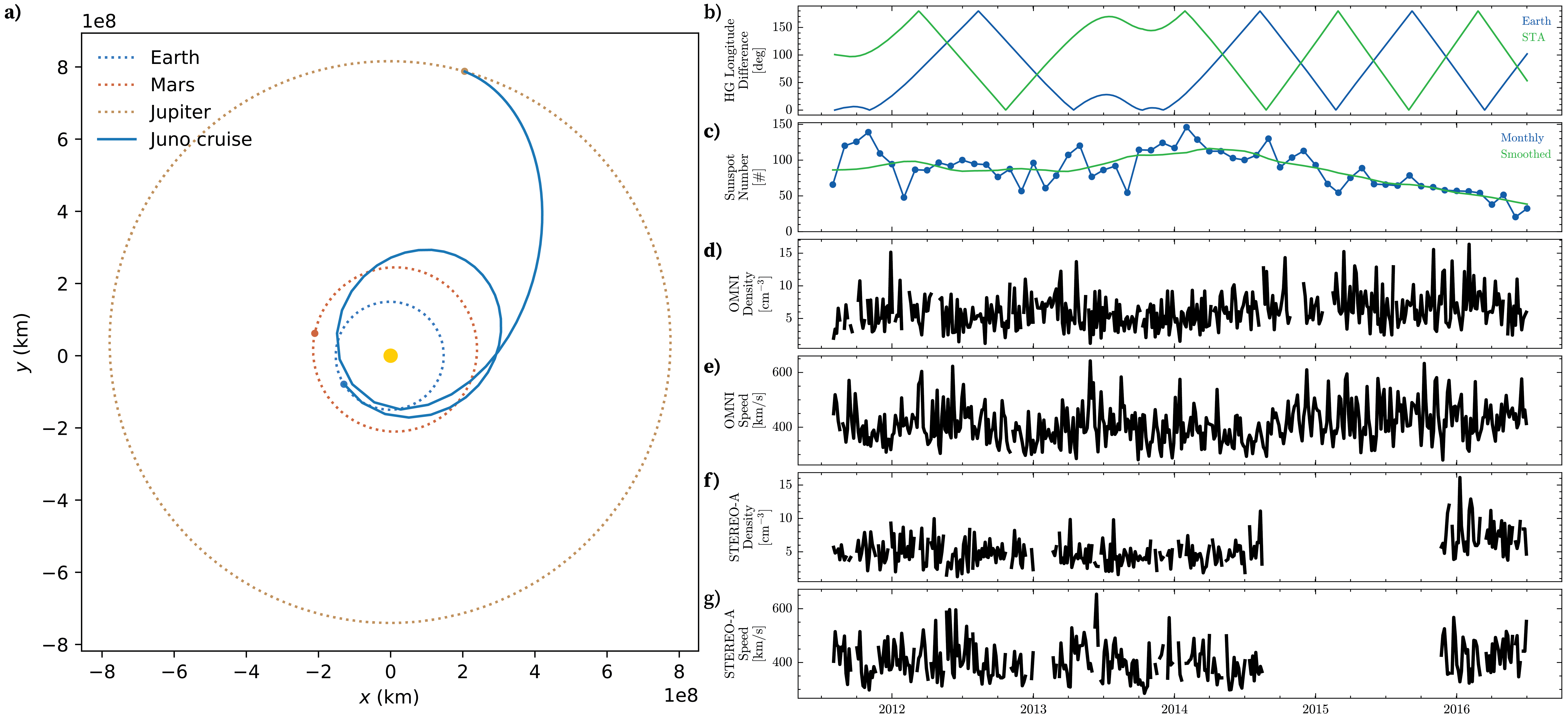

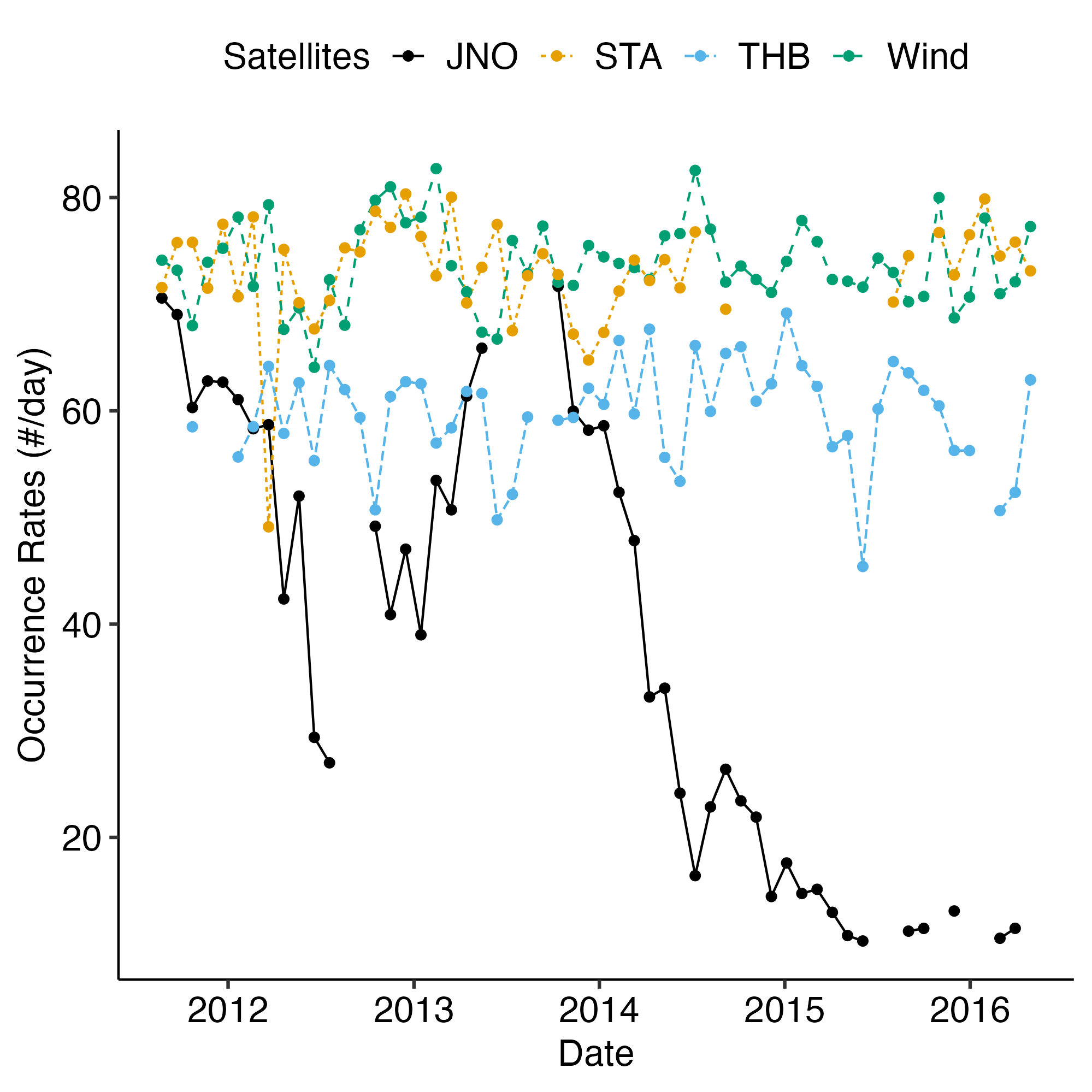

The solar wind plasma state, as evidenced by the sunspot number (referenced in panel (c) of Figure 2), plays a crucial role in understanding the dynamics of discontinuities. During the initial phase of the JUNO mission, the sunspot number reached its peak, indicating a period of heightened solar activity. However, by the end of the mission’s cruise phase, there was a significant decline in solar activity. This variation underscores the importance of calibrating the discontinuity properties in relation to solar activity levels to account for temporal fluctuations.

Further analysis of Figure 2 highlights the significance of the heliographic longitudinal difference between the Juno mission and Earth as well as the STEREO-A mission. Specifically, when there is a substantial longitudinal difference between Juno and Earth, the difference between Juno and STEREO-A tends to be minimal, and vice versa. This longitudinal discrepancy between Earth and STEREO-A ensures comprehensive coverage of the plasma en route to Juno.

Datasets from missions such as STEREO, ARTEMIS, and WIND will complement observations from PSP and Juno, offering a broader contextual perspective on heliospheric conditions and enabling a multi-point analysis of discontinuity properties (Velli et al. 2020). The table below summarizes the time resolution of magnetic field and plasma data for PSP, Juno, Wind, ARTEMIS, and STEREO. However, since Juno does not provide direct plasma measurements, we will estimate the spatial scale (thickness) of discontinuities using solar wind speed derived from solar wind propagation models. Specifically, we will employ the Two-Dimensional Outer Heliosphere Solar Wind Modeling (MSWIM2D) (Keebler et al. 2022) to determine the ion bulk velocity (\(v\)) and plasma density (\(n\)) at Juno’s location. This model, which utilizes the BATSRUS MHD solver, simulates the solar wind propagation from 1 to 75 astronomical units (AU) in the ecliptic plane, effectively covering the region pertinent to our study. The MSWIM2D model provides output data with an hourly time resolution as shown in Figure 6. The comparison of magnetic field magnitudes from MSWIM2D with those measured by Juno, after averaging to the same time resolution, reveals a strong correlation, confirming the model’s reliability.

| Mission | δt(B) | δt(plasma) |

|---|---|---|

| Parker Solar Probe | ~200 Hz | 0.25-1 Hz |

| Juno | 1 Hz | 1 hour |

| ARTEMIS | 5 Hz | 0.25 Hz |

| WIND | 11 Hz | 1 Hz |

| STEREO | 8 Hz | 1 min |

Discontinuity Identification and Analysis:

This first step in understanding the evolution of solar wind discontinuities involves identifying and characterizing these structures. We will adopt Liu’s method (Liu et al. 2022) for this purpose. This approach provides better compatibility for discontinuities with small magnetic field changes and demonstrates greater robustness for conditions in the outer heliosphere compared to traditional methods, namely the B-criterion (Burlaga 1969) and the TS-criterion (Tsurutani and Smith 1979). For each sampling time \(t\), we define three intervals: the pre-interval \([-1,-1/2]\cdot τ+t\), the middle interval \([-1/2,1/2]\cdot τ+t\), and the post-interval \([1/2,1]\cdot τ+t\), where \(τ\) represents time lags. The magnetic field timeseries in these three intervals are labeled as \({\mathbf B}_-\), \({\mathbf B}_0\), and \({\mathbf B}_+\), respectively. To identify a discontinuity, the following three conditions must be met:

\[ \begin{aligned} \sigma({\mathbf B}_0) &> 2\max\left(\sigma({\mathbf B}_-), \sigma({\mathbf B}_+)\right) \\ \sigma\left({\mathbf B}_-+{\mathbf B}_+\right) &>\sigma({\mathbf B}_-)+\sigma({\mathbf B}_+) \\ |\Delta {\mathbf B}| &>|{\mathbf B}_{bg}|/10 \end{aligned} \]

Here, \(\sigma\) denotes the standard deviation, \({\mathbf B}_{bg}\) represents the background magnetic field magnitude, and \(\Delta {\mathbf B}={\mathbf B}(t+τ/2)-{\mathbf B}(t-τ/2)\). The first two conditions ensure that the field changes are distinguishable from stochastic fluctuations, while the third condition serves as a supplementary measure to reduce recognition uncertainty. Notably, this method shares certain similarities with the Partial Variance of Increments (PVI) approach for identifying coherent structures, as both calculate indices based on standard deviations (with this method focusing on the standard deviation of the magnetic field, and PVI on magnetic field increments). However, this method is better suited for discontinuity identification by comparing data within neighboring time windows rather than across a correlation scale (an unknown quantity that may vary with radial distance and solar wind conditions). As a result, this approach effectively excludes wave-like coherent structures, eliminating the need for manual inspection and bypassing the necessity of grouping continuous clusters of high-PVI points as in PVI analysis.

Subsequently, for each identified discontinuity, we calculate the distance matrix of the time series sequence (the distance between each pair of magnetic field vectors) to ascertain its leading and trailing edges. After that, we use the minimum or maximum variance analysis (MVA) analysis (Bengt U. Ö. Sonnerup and Scheible 1998; B. U. Ö. Sonnerup and Cahill Jr. 1967) to transform the magnetic field into the boundary normal (LMN) coordinate system. The main (most varying) magnetic field component, \(B_l\), is then fitted by a hyperbolic tangent function to extract the parameters to properly describe the discontinuity Equation 1. Then we combine the magnetic field data and plasma data to obtain the thickness and the current density of the discontinuity.

\[ B_l(t) = B_{l0} \tanh\left(\frac{t - t_0}{\Delta T}\right) + c_l \tag{1}\]

While previous studies (Vasko et al. 2021, 2022), typically using data from a single spacecraft, often calculate current intensity by taking the derivative of the time series, our study must account for the varying time resolutions of different spacecraft. To address this, we fit the data to achieve a more precise representation of the peak current density, \(J_m = - \frac{1}{\mu_0 V_n} \frac{d B_l}{d t}\), thereby minimizing the impact of time resolution discrepancies.

Examples of solar wind discontinuities detected by various spacecraft are illustrated in Figure 3.

Proposed Approach:

Two promising approaches are proposed for studying the evolution of solar wind discontinuities:

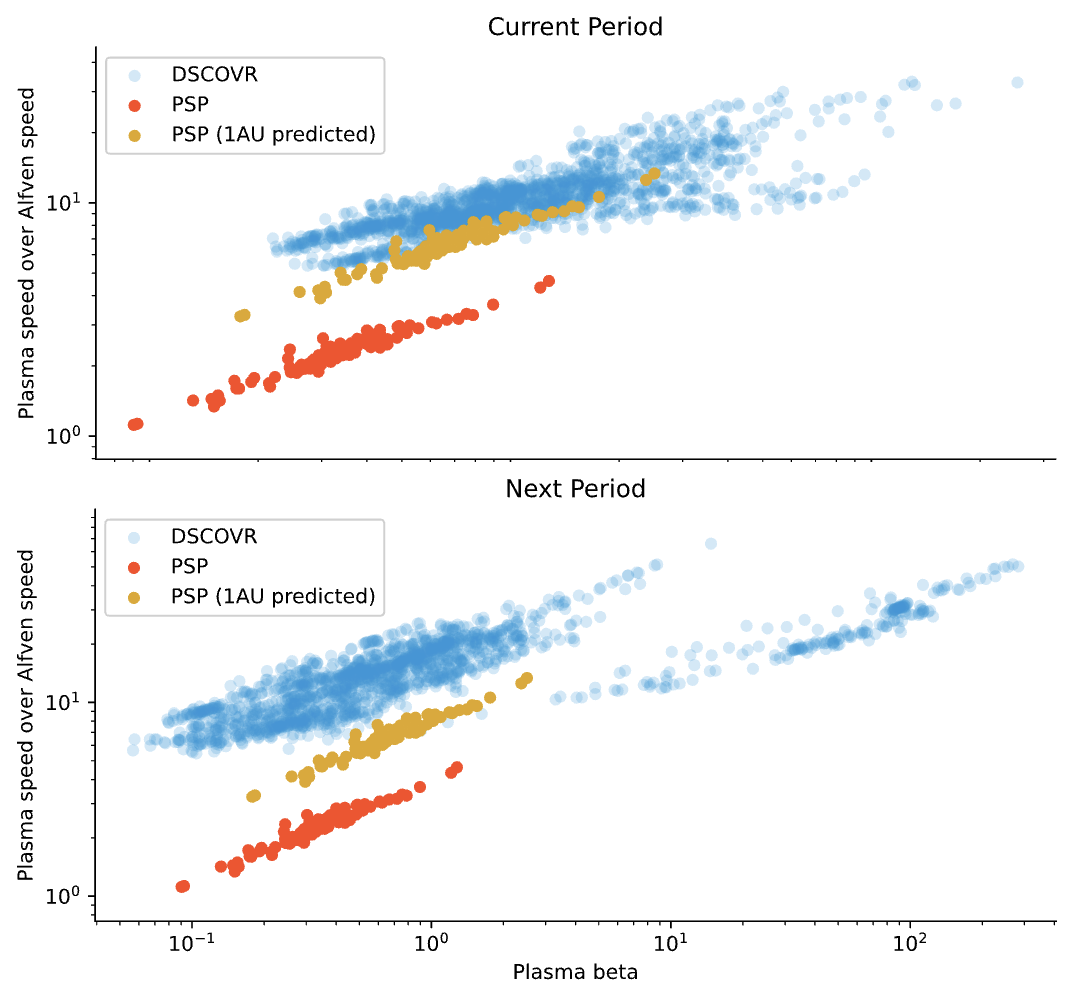

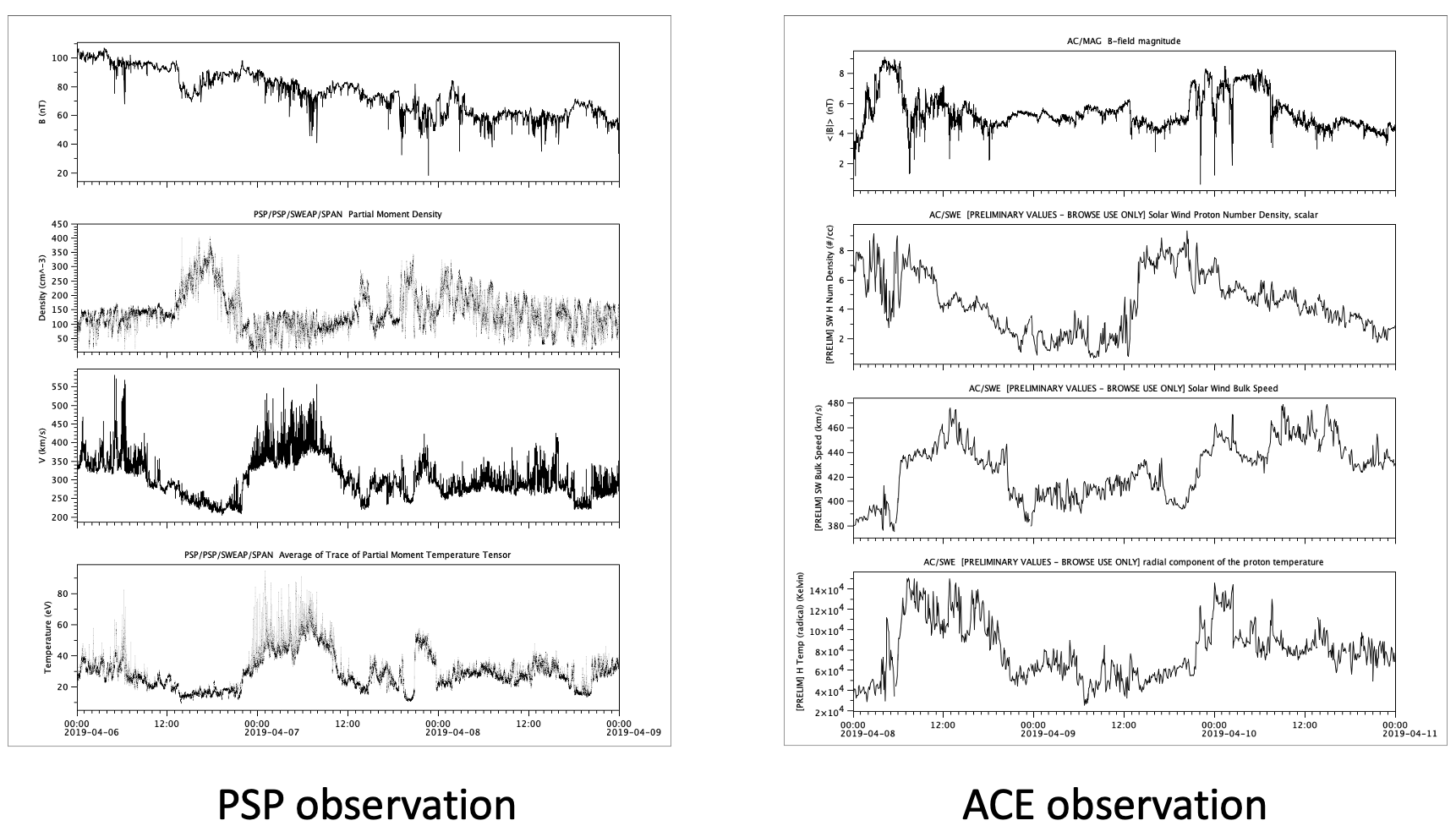

1. Conjunction Events Analysis: This approach involves studying instances where spacecraft are simultaneously aligned along the same spiral field line, thus measuring solar wind emanating from the same solar surface region, or positioned to measure the same solar wind plasma (Velli et al. 2020). The latter alignment is determined by the difference in radial distance, \(\delta R\), corresponding to the solar wind travel time, \(\tau = \delta R / V_{sw}\). An example demonstrating this approach is presented in Figure 4, showcasing similar trends in magnetic field magnitude, plasma density, velocity, and temperature observed by the Parker Solar Probe (PSP) and the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) during an alignment period in April 2019. Validation is further supported by utilizing the statistical plasma expansion model (Perrone et al. 2019), where the plasma properties measured by PSP and projected to the ACE location exhibit good agreement with actual ACE measurements, as depicted in Figure 7. This confirms the validity of the alignment approach for studying solar wind discontinuities.

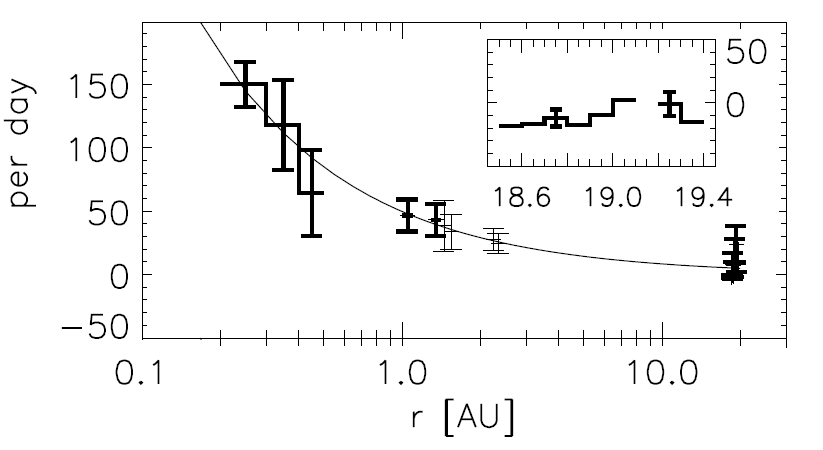

2. Comparative Analysis: This approach leverages extensive data collected over the years to compare solar wind discontinuities observed by different spacecraft at various radial distances. Due to the Sun’s rapid rotation, solar wind plasma emitted from a single region on the solar surface sweeps across the entire heliosphere within a solar rotation period of 27 days. By utilizing solar wind measurements at 1 AU from STEREO, ARTEMIS, and WIND, and comparing these with data from Juno and PSP, it is possible to distinguish between the effects of temporal variations in solar wind and those due to spatial variations (associated with radial distance from the Sun) in the occurrence rate and characteristics of discontinuities. An example of such a comparison for the occurrence rate is depicted in Figure 5, where the number of discontinuities measured per day by different spacecraft missions is plotted.

In the proposed study, we will expand this comparison to include the properties of discontinuities, such as thickness, strength (current density), and orientation.

This extension will enable us to grasp how these features evolve with radial distance from the Sun and how they relate to the local plasma properties. Examining these properties is crucial for understanding the generation of discontinuities. Borovsky (2008) argued that solar wind discontinuities act as static boundaries between flux tubes originating at the solar surface and they are convected passively from the source regions. However, Greco et al. (2009), by examining the waiting time distribution of magnetic field increments, discovered a good agreement between MHD simulations and observations. This finding suggests that discontinuities stem from intermittent MHD turbulence, indicating local generation. If turbulence theory holds true, discontinuities properties should align with local plasma parameters; conversely, if propagation theory is accurate, discontinuity properties should be consistent with the solar wind expansion model. Studying these properties will provide insights into the physical mechanisms governing discontinuity formation and spatial evolution as solar wind propagates through the heliosphere.

Summary

This research project adopts a comprehensive approach to unravel the complex characteristics of solar wind discontinuities, seeking to shed light on their fundamental characteristics. By utilizing big data from multiple spacecraft missions throughout the heliosphere, we aim to examine the temporal variations in these properties driven by solar activity, as well as the spatial variations influenced by radial distance from the Sun. Our goal is to infer the intricate processes governing the evolution of magnetic discontinuities, a key component of magnetic field turbulence and a crucial interface for charged particle acceleration.

Figures